|

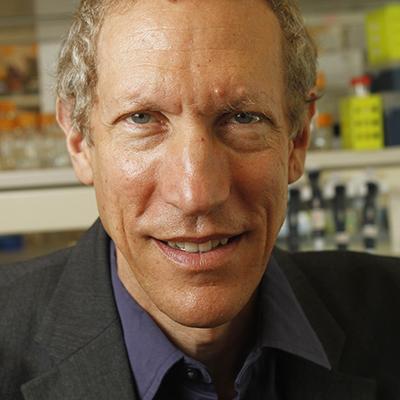

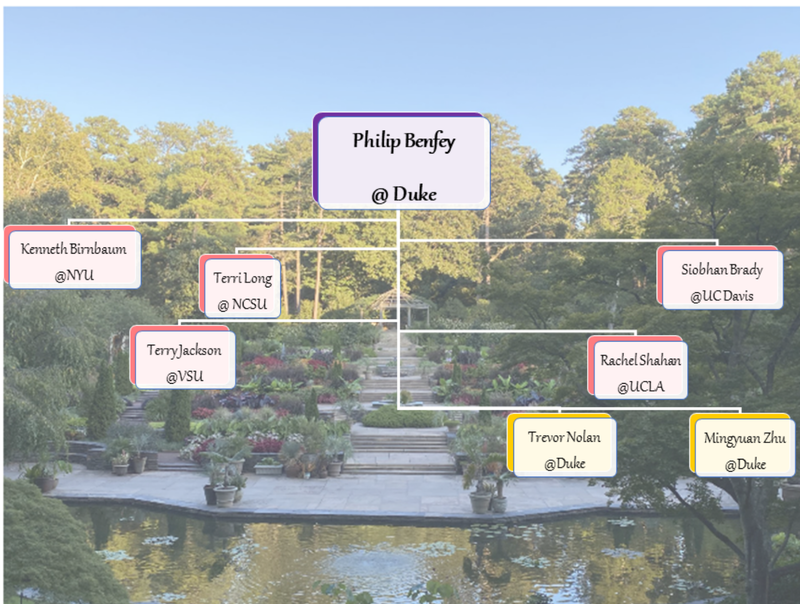

Authors: Rachel Shahan, Trevor Nolan, Mingyuan Zhu Philip N. Benfey, an accomplished plant developmental biologist and mentor extraordinaire, passed away on September 26th, 2023. He was 70. Philip’s creativity, entrepreneurial spirit, enthusiasm for collaboration, and dedication to his mentees has left an indelible mark on the plant science community. Philip is survived by his wife, Elisabeth, and two sons, Sam and Julian. Philip began his independent career at The Rockefeller University in 1990. He moved to New York University in 1991 where he rose through the ranks to Full Professor. In 2002, Philip moved his lab to Duke University—where he chaired the Biology Department from 2002 to 2007—and subsequently led the Duke Center for Systems Biology until 2014. While at Duke, Philip was named the Paul Kramer Distinguished Professor of Biology in 2003, a fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 2004, elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2010, and appointed an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in 2011. As a mentor, Philip taught his students and postdocs to be rigorous scientists and critical thinkers; he also encouraged creativity and out-of-the-box ideas. In total, over 80 postdocs and graduate students received their training in the Benfey lab. As a scientist, Philip was fascinated by fundamental developmental questions such as, “how do cells acquire their identities?” and, “how do tissues create a functional organ?”. To investigate the genes involved in these processes, Philip chose a simple but elegant model: the Arabidopsis root. Using this system, and eventually the roots of other plant species, the Benfey lab produced pioneering research for nearly four decades. Philip was an enthusiastic proponent of new technologies. His lab's innovative use of fluorescence-activated cell sorting followed by microarray and RNA-seq analyses led to the first spatiotemporal maps of gene expression in plant roots (1,2). These advances were pivotal in enabling the annotation and interpretation of the first plant single cell RNA-seq datasets, which were generated from Arabidopsis roots. Philip's contributions helped lay the groundwork for the initiatives of the Plant Cell Atlas, both through the thriving network of researchers trained in his lab (Fig 1) and the biological and technological breakthroughs that he spearheaded. Philip's enthusiasm for the adoption of single-cell transcriptomics led to the creation of detailed transcriptional maps of Arabidopsis and rice roots. His long-term interest in imaging technologies resulted in the development of a custom light sheet microscope to quantitatively track transcription factor dynamics underlying formative asymmetric cell divisions in live roots. These efforts enabled the Benfey lab to generate new insights into cell identity specification, molecular phenotypes in developmental mutants, cell type-specific hormone responses, and root-soil interactions (3,4,5). In alignment with the PCA goals to produce community resources, all raw and processed sequencing data, metadata, and code is publicly available alongside each of these recent publications. The comments that follow are reflections on Philip's significant influence on the Plant Cell Atlas community, particularly regarding advancements in single-cell genomics. References:

Testimonials: I joined Philip’s lab as a postdoc in June 2018. At the end of my first week, I attended the symposium organized by Benfey Lab alumni in honor of Philip’s 65th birthday. I was struck not only by the outstanding research in the labs of Philip’s former trainees but also by the camaraderie and collaboration between lab alumni. It was clear that Philip’s lab produced an ecosystem of researchers who freely share ideas, resources, and expertise. This collective spirit is also reflected in the Plant Cell Atlas community. As the co-chair of the PCA Single-Cell Sequencing committee, I am proud to contribute to PCA initiatives together with several of Philip’s former trainees and many colleagues who worked closely with Philip. Based on my experiences with single cell RNA-seq protocol development and data generation as a postdoc, I am especially committed to the PCA’s goal of openly sharing resources and expertise. To this end, the Single-Cell Sequencing committee organized two workshops this year to share information about experimental design, sample preparation, and data analysis. While I will miss Philip and his outstanding mentorship, I will carry the lessons that I learned as his postdoc with me as I continue to contribute to the PCA and as I start my own lab at UCLA. - Rachel Shahan Single-cell genomics was just ramping up in plants when I came to Philip’s lab. At the time, most researchers were profiling a handful of samples, mostly from untreated roots. In his typical style, Philip proposed the bold idea to perform time course scRNA-seq of environmental responses. Since such a time course hadn’t yet been performed and my background was in brassinosteroid signaling, we decided to examine brassinosteroid responses as a test case. Although we initially expected that we would simply recover known sites of action, we were pleasantly surprised when an overlooked cell type seemed to be responding at a particular developmental stage. This is something that would have been difficult to pick up with previous technologies that conflated cell type and/or developmental stage. This exemplifies Philip’s approach to research: he shattered paradigms by pioneering technologies, listening to the data, and appreciating the unexpected. Philip was equally enthusiastic as spatial technologies started to be applied to plants; he encouraged me to seek training to apply these exciting techniques to my interests in root growth and cell elongation. I will be forever grateful for the years I spent in Philip’s lab. His vision, kindness, and ability to plan strategically were unmatched. He demonstrated what it means to be a leader and that it’s possible to be a top-notch scientist while having a thriving life outside the lab. - Trevor Nolan When I joined the Benfey lab in 2020, the single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq) on rice roots was already underway, led by two talented Postdocs Isaiah Taylor and Trevor Nolan. It has been a great pleasure joining the team and learning everything from scratch. Over the course of a challenging yet rewarding year, we harvested tens of thousands of high-quality cells to construct a reference root atlas. However, a significant hurdle emerged: confidently annotating the identified cell clusters in our scRNA-seq atlas. Philip, with his insightful research instincts, initiated a collaboration with Resolve Biosciences. This led to the pioneering application of a multiplexed fluorescence in situ hybridization technology, Molecular Cartography, on rice roots. I vividly recall Philip's enthusiasm, evident in his frequent email checks on the day we received the data and his prompt response to my updates that evening. We validated over 40 reliable markers with just two rounds of experiments. However, this was not the end of our journey. Philip, true to his nature as a trailblazer, sought collaboration with soil experts Malcolm Bennett and Bipin Pandey. Together, we pioneered the application of both single-cell and spatial transcriptomics to roots grown in soils, unveiling cell-specific responses to soil compaction at the single-cell level. Engaging in this groundbreaking work not only allows me to learn new techniques and delve into specific scientific questions but also instills in me the mindset of continuously challenging myself to explore uncharted territories. I am deeply grateful for the years spent together with Philip. His unwavering dedication to pushing the boundaries of science motivates me to keep going. - Mingyuan Zhu Philip could hold court with his views on research and life, but he also practiced the art of understated phrases and gestures that spoke volumes. He could steer the lab’s projects with a few choice words, such as ”It’s in the realm of possibilities.” In some contexts, that was an “I doubt that can work” and, in others, an indication to “give it a try”. I was working for at least two and half years on our protoplast generation cell sorting marker idea (it was clearly in the give-it-a-try realm of possibilities category). Two trips to David Galbraith’s lab in Arizona. Two failed proposals to NSF and NIH. We weren’t sure it was working. Our best colleagues were skeptical. But we adjusted the methods and lightning struck. I brought the in situ hybridization to Philip’s little office overlooking Greene Street at NYU with the definitive evidence that it worked, proudly plopped the in situs on his desk, and stood waiting for his reaction. He stared down at the in situ printouts, he didn’t say a word, he didn’t lift his head. He just held up one of his extra-long arms for a victory handshake. Twenty years later I don’t remember the moment I looked at the in situs under the microscope, but I do remember the handshake. On my toughest days, it always makes me smile. - Ken Birnbaum As a graduate student, I remember reading the too-incredible-to-believe papers coming out of the Benfey lab, describing how cell type-specific expression could be profiled using a handful of transgenic lines and FACS. At the time I thought it was crazy. Little did I know that this prescient technology would enable an entire revolution in how we study gene expression in plants, and that I would turn into a fierce advocate for the approach. I had the fantastic opportunity to meet Philip at a conference he and I were both presenting at, incidentally, on the same topic (integration of plant single-cell datasets), at the same time. I got an ominous email the day before my presentation, asking to meet. At first, I was terrified that I was now competing with not only an amazing scientist, but a Howard Hughes Investigator to boot, and was about to get completely scooped. Instead, he expressed a desire to collaborate, as he felt that it was better to build coalitions rather than compete, especially when we can help each other. This was instantly disarming, and resulted in one of the most fun experiences I’ve had in my scientific career. I think this collaborative spirit also permeates the generations of scientists that trained in Philip’s lab, many of whom are as talented, kind and collaborative as he was. He was a true asset to the community, and will be sorely missed. - Benjamin Cole There are many things to admire about Philip Benfey, but one thing that stood out for me is how big he thought. I attended a seminar of his as I was about to go on the job market for faculty positions. He had this fantastic line: “What is your twenty year question?”. In other words, what area could you spend your whole career working on, and perhaps not even solve. As a postdoc, I wasn’t used to thinking at such a grand scale. We tend to think experiment-to-experiment, maybe grant-to-grant at most. To know that the job requires rewiring your thinking to operate at this scale was very instructive for me. I still use his line in career workshops to postdocs and grad students! Philip will indeed be missed. - Aman Husbands I was super-inspired by Philip Benfey, Ken Birnbaum and colleagues’ 2003 paper. Although I had just set up the server that would eventually become the BAR, it would be a few more years before I invented the eFP Browser. One of the first views that we created for the Arabidopsis eFP Browser was a cell-type-specific view that included the Birnbaum et al. 2003 data. I was also inspired to actually do some cell-type-specific expression profiling and even managed to publish in the area, after training in Ken Birnbaum’s lab at NYU (with the help of Bastiaan Bargmann). The most detailed FACS-based root data set that we included in the eFP Browser was the Brady~Benfey paper from 2007. Soooo much cool data! I was fortunate enough to meet Philip in 2008 - he kindly agreed to come to the Canadian Plant Genomics Workshop I was co-organizing that year. His harrowing tale at a dinner during the workshop of being in NYC during 9/11 has stuck with me, as has his collaborative spirit. RIP Philip, you will be missed. - Nicholas Provart As a PhD student at Duke University, Dr. Ashley Chi insisted that if I wanted to join a plant biology lab then I must go to The Benfey Lab. I remembered seeing Philip during interview weekend with one of his graduate students, Todd Twigg showing off the Root Array. I thought it was a cool concept and gadget so I set up a meeting and he gave me a much needed final rotation. It is one of the best decisions I ever made. I was able to join the lab of a titan in the field. I spent my best years in the Benfey lab surrounded by people I absolutely loved. I cherish every memory and moment I spent in his company.

I remember his lessons and words to me vividly. Philip Benfey gave me all the tools I needed to succeed and achieve my dream of becoming a geneticist. He believed in me when many of the leaders of my program were ready to give up on me. Philip refused. He recognized that my difficulties could be overcome and he had the resources and people in his lab that could prove it. That’s exactly what we did. It wasn’t long before I began to excel and make a bit of a name for myself by utilizing skills that simply needed to be focused and channeled properly. My peers were telling tales of desperation and disdain for their advisors, lab, and projects while I told a story of living my best life – being surrounded by brilliance and compassion everyday. In the Benfey lab, I felt at home surrounded by family and it was the only place I wanted to be. Philip is more than a mentor or someone to look up to, he is a clear depiction of countless qualities a person would want to embody and employ in themselves. Philip became a role model to me and remains one of only two or three I have ever had. He remains so to this day and I strive to live up to his guidance over the years. Calm, cool, and collected – Philip always said the right thing, the right way, at the right time. I can never forget that with one word, “Very”, he broke me down and inspired me to collect myself, improve, and continue to chase my dream simultaneously. He was an imposing figure yet delicate. Despite knowing he was going to be easy and kind when you met with him, you still were nervous. Always nervous. Nervous that you would say the wrong thing or somehow let him down. You always wanted to bring your best to his desk and attention. I can never thank him enough for all he has done for me. I can never show the gratitude and thanks that I have for him. He is the greatest and will forever be dear to me. - Terry L. Jackson

0 Comments

|

Archives

December 2023

Categories |

MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

“The Plant Cell Atlas operates predominantly out of Michigan State University. We acknowledge that Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg – the Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and hold Michigan State University accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.”

“The Plant Cell Atlas operates predominantly out of Michigan State University. We acknowledge that Michigan State University occupies the ancestral, traditional, and contemporary Lands of the Anishinaabeg – the Three Fires Confederacy of Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi peoples. We affirm Indigenous sovereignty and hold Michigan State University accountable to the needs of American Indian and Indigenous peoples.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed