Marie Clark Taylor

|

Marie Clark Taylor was born in Pennsylvania on February 16th, 1911, when the world was still highly segregated. Yet, she would go on to become one of the United States’ most successful educators and demonstrate how BIPOC women could shape the world. She was the first Black woman to get a Ph.D. in botany, the first woman of any race to receive a Ph.D. of science from Fordham University, and one of the world’s most prominent Black educators in Science. She was even requested by President Lyndon B. Johnson to expand her teaching internationally.

Her research focused on photomorphogenesis: the study of how light influences plant development. Her experiments investigated how photoperiods, or precise lengths of light exposure, affected the development of floral buds. She returned to Howard University’s botany department in 1945 to become an assistant professor, and became chair of the department soon after, which held until she retired in 1976. Taylor renovated science education by adopting a hands-on approach to learning. Taylor advocated for using live plant cells to study life in real-time using light microscopes. Because the cross-sections of cells were still living, students could watch the processes that made life possible – a stark contrast to the dead preserved tissues typically used before then. Grants from the National Science Foundation allowed her to disseminate her methods, and the use of live plant tissue became the educational standard. Taylor died in December 1990, leaving a legacy that inspires students to this day. |

Additional Information

Woman of Firsts: Marie Clark Taylor, Women in Horticulture

Fordham's First Female Ph.D., The Fordham Ram

Celebrating Black History Month: Marie Clark Taylor, Desert Botanical Garden

Woman of Firsts: Marie Clark Taylor, Women in Horticulture

Fordham's First Female Ph.D., The Fordham Ram

Celebrating Black History Month: Marie Clark Taylor, Desert Botanical Garden

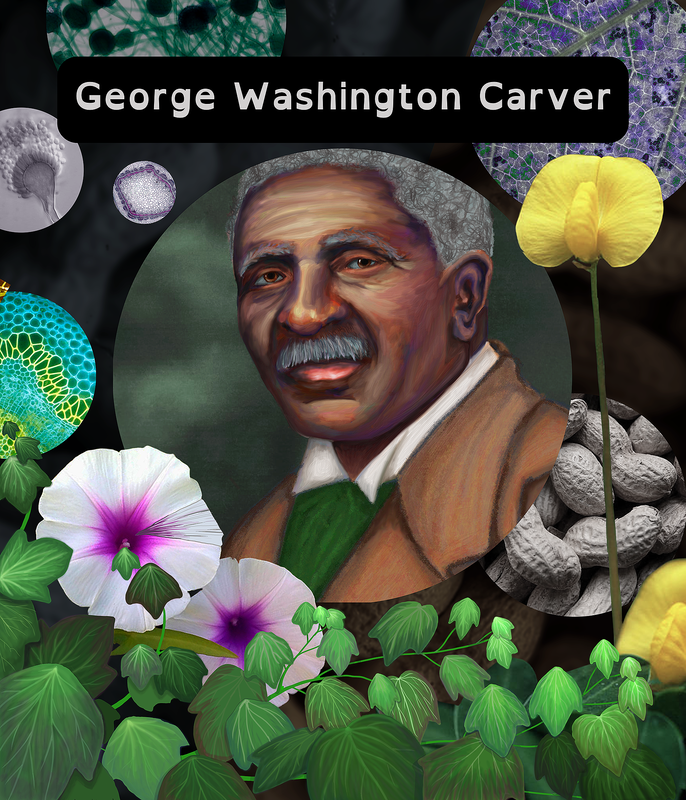

George Washington Carver

|

George Washington Carver was born in Missouri around 1864. Carver took interest in plants at a young age and was nicknamed “the plant doctor” by neighbors because of his understanding of and passion for plants. As a teen, Carver decided to put himself through school in Minneapolis, Kansas, doing domestic work for money. In school he expanded his drawing skills and became skilled in the visual arts. He was accepted to Simpson college to study art, but rejected once they discovered Carver was Black. Carver persevered, and eventually switched to the sciences: Carver earned a bachelor’s degree in 1894 from Iowa State. He studied fungal infections and soybeans to great success, and began the pursuit of a graduate degree after encouragement from his professors. After earning his masters of Agriculture in 1896, he moved to Tuskegee University, where Booker T. Washington offered him a position as director of an Agricultural Experiment Station. Carver independently invented crop rotation of peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes, similar to the three sisters of First Nation agricultural practices. These practices restored the soil’s nitrogen content while providing a nutritious diet for the farmers.

Carver’s most famous success was with peanuts, inventing a use for every part of the plant. The initial market for peanut products was very small, but Carver persevered. He met with the House of Representatives in 1921 to argue for a tariff on peanuts paving the way for peanuts to become the cash crop of the South. His work gained worldwide recognition. In 1916 Carver was elected to Britain's Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce and he later received the Spingarn Medal in 1923. Posthumously Carver was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame and was given a national monument - the first dedicated to a Black American. |

Additional Information

In Search of George Washington Carver's True Legacy, Smithsonian Magazine

George Washington Carver, Science History Institute

George Washington Carver: American Agricultural Chemist, Britannica Encyclopedia

George Washington Carver, History Channel

List of Products Made from Peanut by George Washington Carver, Tuskegee University

In Search of George Washington Carver's True Legacy, Smithsonian Magazine

George Washington Carver, Science History Institute

George Washington Carver: American Agricultural Chemist, Britannica Encyclopedia

George Washington Carver, History Channel

List of Products Made from Peanut by George Washington Carver, Tuskegee University

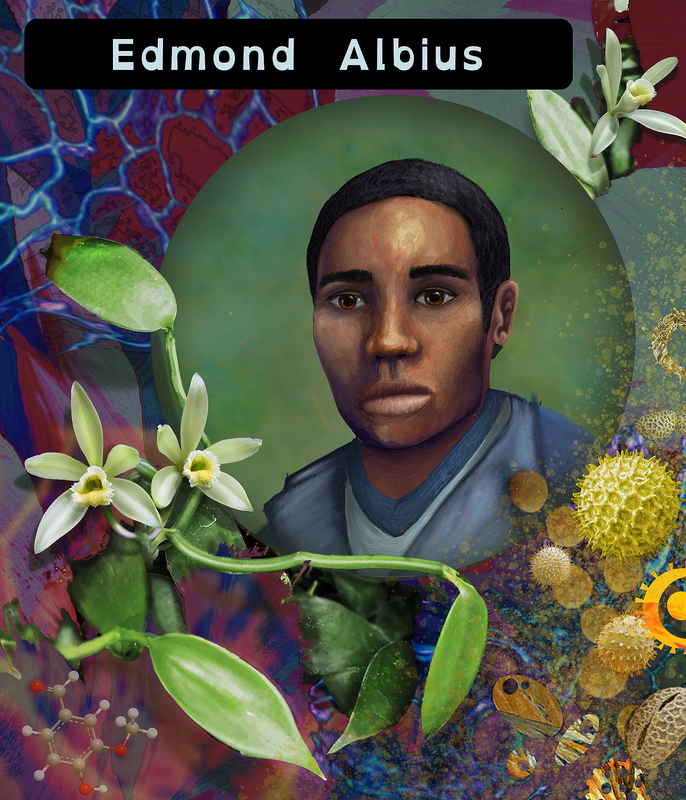

Edmond Albius

|

Vanillin, the compound that gives desserts around the globe a delicious taste, comes from an orchid native to Mexico - vanilla. In its native habitat, it is pollinated by the specialized beaks of hummingbirds, and the flowers only last for a day. That, combined with the multi-year process it takes to produce one vanilla bean, makes vanilla extremely difficult to cultivate. Vanilla beans today mostly come from Madagascar, with over 70,000 farmers involved in its production, but before 1840 it was only grown in select places in Mexico. This change is all thanks to Edmond Albius.

Edmond was born a slave in 1829 in St. Suzanne, Réunion - a French island near Madagascar. Sent to assist the botanist Fereol Bellier-Beaumont as a child, Edmond was taught how to care for Beaumont’s many plants, including hand pollination. By then vanilla had been cultivated globally, but it would not grow beans – the desired fruit of the plant. This was because it had no native pollinators on these distant plantations that could fertilize the flowers. Edmond, curious why this was, closely examined the flowers and found the stigma, the plant’s pollen receiving organ, and noticed a leafy lid covering it. Edmond opened the flap using blades of grass, and deposited pollen into the flower. Weeks later, as vanilla beans hung from the vines, Edmond’s discovery became the start of the vanilla industry. “It is entirely due to him,” quoted Fereol, that Réunion became a prosperous country. Edmond was then freed and given the last name Albius, but he never received any profits from his discovery. After a brief stint abroad he married and moved back to Réunion, where he lived until his death in 1880 at the age of 51. A century later, a statue of Albius was built in Réunion that honors his contribution to science, and the sweet taste of vanilla. |